Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) Injury

What is the Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL)?

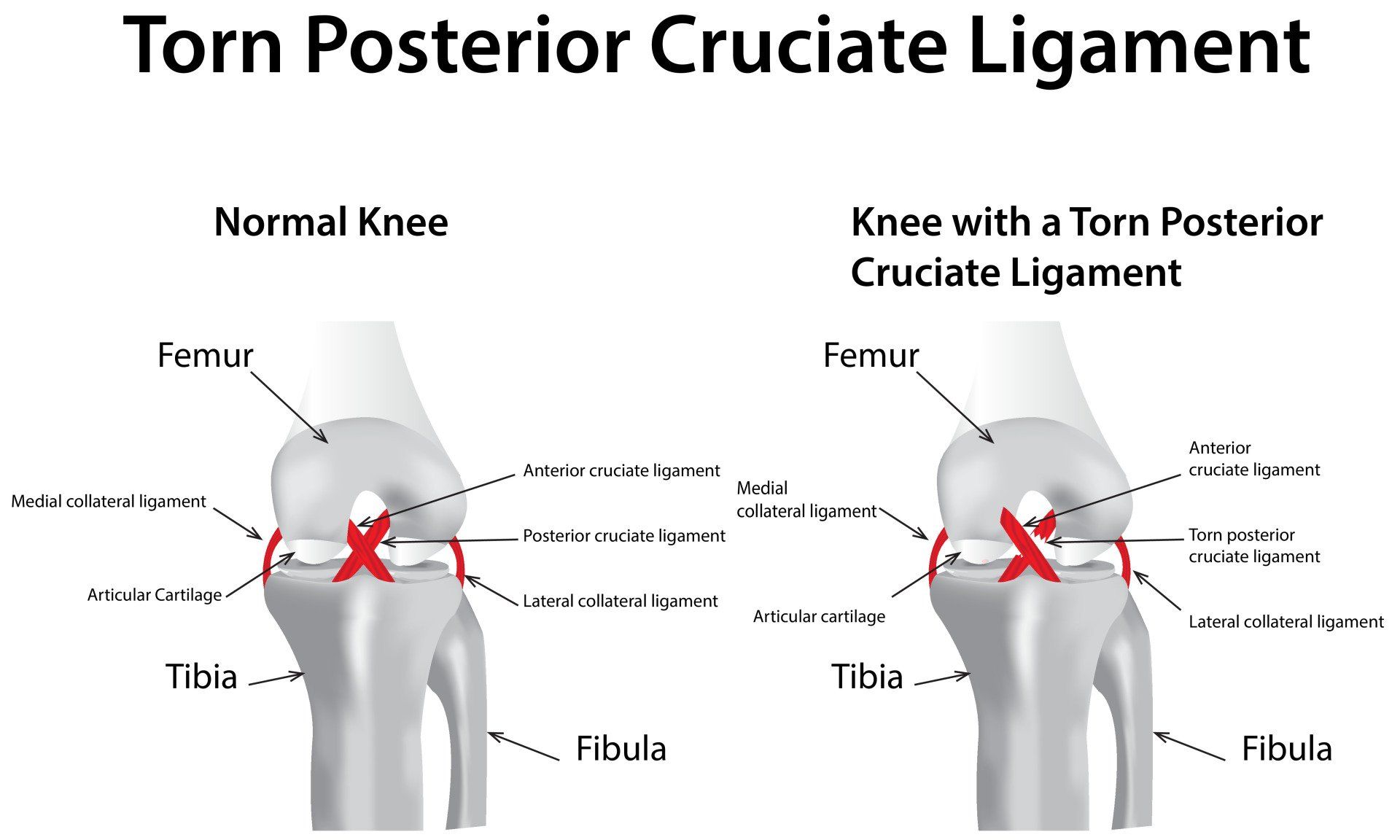

- The Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) is the strongest ligament in the knee

- The PCL extends from the posterior (backend) part of the central upper tibia to the medial (inner) femoral condyle

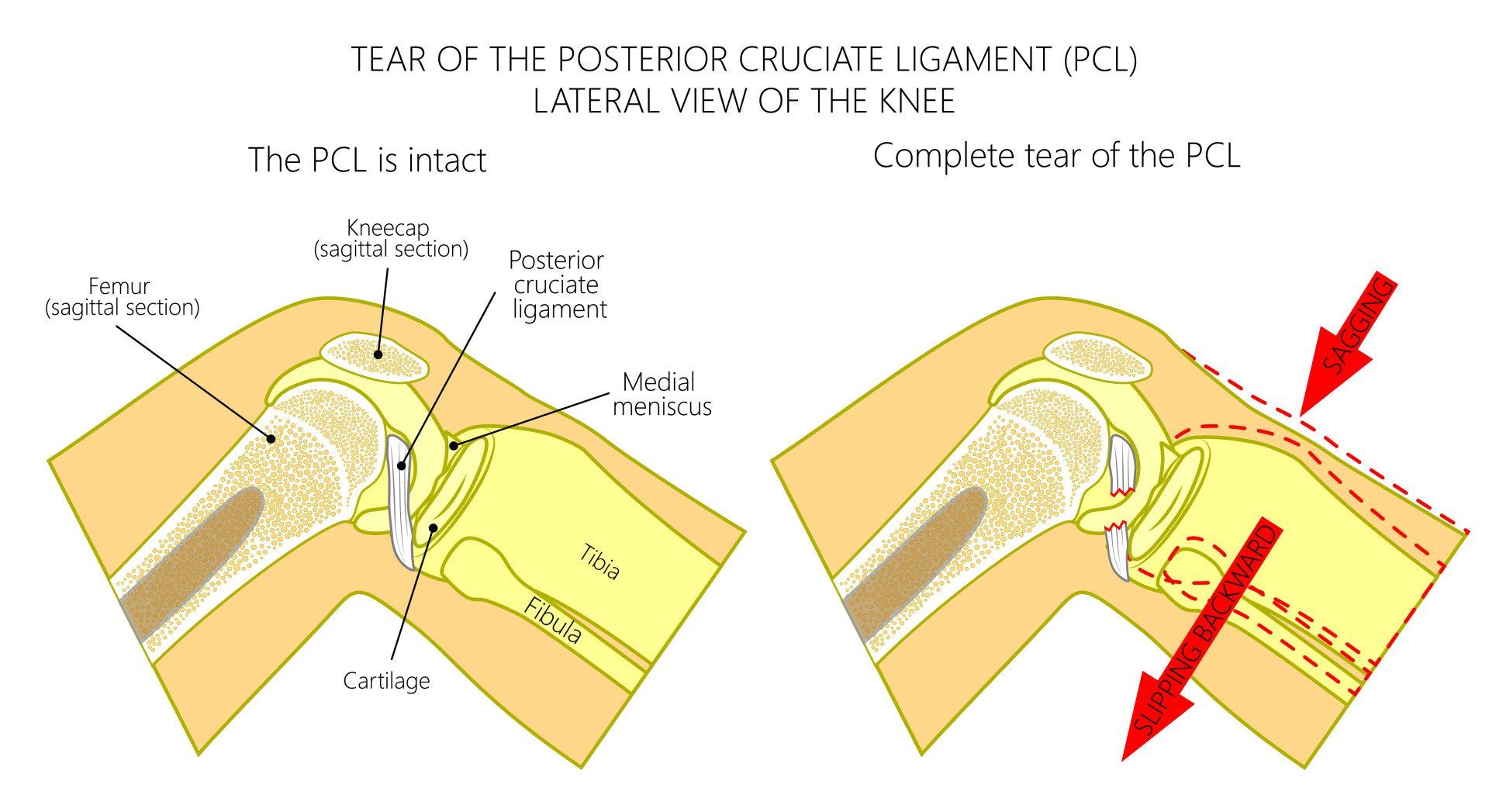

- The main function of the PCL is to prevent the tibia moving backwards (posterior) in relation to the femur

- The PCL is a secondary stabiliser to internal and external rotation of the tibia in relation to the femur

- The PCL is not commonly injured

- PCL injuries make up less than 20% of all knee injuries

- PCL injury is thought to affect 2 per 100,000 people every year

- In comparison an ACL injury affects 1 in 3,500 people every year

What is the size of the PCL?

- The PCL is 11-13 mm in diameter

- The PCL is 35-38 mm in length

Why is the PCL injured far less commonly than the ACL?

- The PCL is much stronger than the ACL

- The reason for this is due to:

- The diameter of the PCL is 1.5 times bigger than the ACL meaning that the ligament itself is much harder to break

- The area of bone that the PCL attaches is three times larger than that of the ACL:

- This means that the PCL attaches much stronger to the tibia and femur than the ACL so it is harder to tear off from these points of attachment

- PCL injury is most commonly caused by a direct blow on the tibia pushing it in a backwards direction in relation to the femur whilst the knee is flexed (bent):

- Dashboard injury:

- This occurs when the tibia hits the dashboard during a road traffic collision

- Fall:

- Landing hard directly onto the tibia with the knee bent

- These mechanisms of injury essentially overstretch and break the PCL by driving the tibia excessively posterior (backward) in relation to the femur

- PCL injuries can also happen with hyperextension or hyperflexion injury but these are less common

- Therefore unlike the ACL where the principle mechanism of injury is non-contact, the PCL is more commonly injured by a large direct blow to the knee (that pushes the tibia backwards)

- Isolated PCL injuries are rare

- >90% of all PCL injuries are associated with other ligament injuries in the knee:

- Posterolateral corner injury

- Multiligament injury

- Knee dislocation

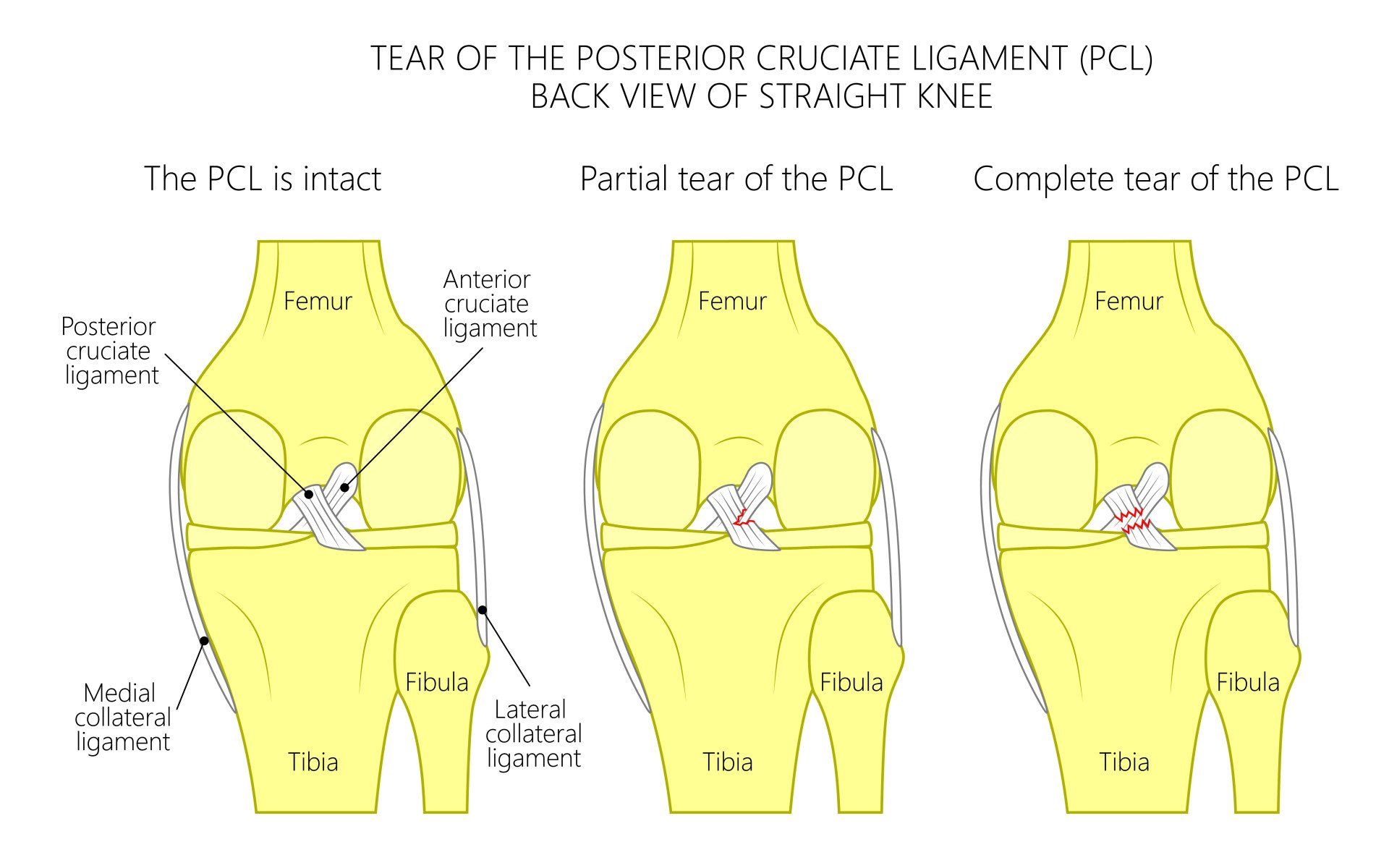

Classification of PCL injury

- This is based on the amount of posterior translation of the tibia relative to the femoral condyles with the knee bent at 90 degrees:

- Grade I: 1-5mm (mild sprain)

- Grade II: 6-10mm (moderate sprain; usually more than 50% torn):

- Grade III: >10mm (complete tear and highest risk of other ligamentous injury)

Symptoms of acute PCL injury

- The symptoms are less marked than with an ACL injury

- This means that patients often present many months later

- Pain and tenderness often quite vague and deep within the knee, but sometimes felt towards the back

- Pain is less marked than an ACL and patient can often walk off the field of play unlike ACL injuries when normally they require assistance

- Tearing can be felt but there is no pop like an ACL tear

- Swelling:

- Knee swelling following a PCL rear is much less than an ACL tear

- Stiffness

- Symptoms will depend on severity of PCL injury:

- Grade I:

- knee will feel stable

- Some pain and discomfort towards the back of the knee

- Grade II:

- PCL will be loose but not commonly associated with instability

- If knee does feel unstable often associated with another ligament injury

- Grade III:

- Commonly associated with other ligament injuries such as lateral collateral ligament (LCL) and posterolateral corner (PLC)

- Knee feels unstable

- Difficulty going downstairs and downhills

Why do PCL injuries tend to present late (i.e a long time after the initial injury)?

- PCL injuries often present late because:

- They are overall not as symptomatic as other ligamentous injuries

- They cause less acute pain, less knee swelling and less rotational instability than an ACL tear

- As a result of PCL injuries being less symptomatic in the acute phase they tend to be found coincidentally when the patient presents with symptoms consequent to a chronic PCL tears

- The consequences of chronic PCL injuries are:

- Increased back and forth sliding of the tibia in relation to the femur

- Increased risk of medial (inner) meniscal tears

- Increased risk of arthritis in the medial (inner) part of the knee:

- At 5 years following a PCL tear 80% of patients will have medial knee arthritis

- Increased risk of arthritis behind the patella (kneecap):

- At 5 years following a PCL tear 50% of patients will have arthritis behind their patella

- Chronic PCL injuries present with:

- Pain at the medial (inner) part of their knee due to medial meniscal tear and medial arthritis

- Pain at the front of the knee due to arthritis behind the patella

- Pain going down stairs and down slopes due to arthritis behind the patella

- Pain and instability on turning, twisting and pivoting

- Pain and instability with decelerating movements

How is a PCL injury diagnosed?

- PCL injury is suggestive from the history of the injury and the examination findings

- X-rays:

- Required to exclude fractures

- Stress radiographs are very helpful:

- These are X-rays taken with pressure on the tibia to push it backward which can then be detected on X-rays and therefore demonstrate the clinical insufficiency of the PCL to prevent this movement

- MRI scan:

- Helps to diagnose PCL injury

- Helps exclude other knee pathology which most often exist such as other ligament, meniscal and cartilage injuries

What is the treatment of a PCL Injury?

- Most isolated Grade I PCL sprains do well with appropriate conservative management:

- Special knee brace must be applied promptly that helps bring the tibia forwards to the neutral position in relation to the femur

- This helps position the tibia in the optimal position for the PCL to heal

- Without the brace the tibia sits too far backwards and the knee will remain slack and unstable

- Extensive physiotherapy rehabilitation focusing mainly on quadriceps strength

- Most Grade III (complete) tears require prompt PCL reconstruction

- There is increasing evidence that Grade II PCL injuries especially those that have symptomatic instability should be surgically treated in order to avoid early knee degeneration

- Bracing of knees with chronic PCL injuries will not aid or improve PCL healing but can provide symptomatic relief

- The presence of other ligament injuries in addition to the PCL tear then surgery tends to be the recommended option

- If at the time of PCL reconstruction other ligament injuries are not addressed then there is high risk of failure

What is the prognosis following a PCL tear?

- Most people do well following a PCL injury if managed correctly

- Chronic PCL deficient knee poses increased risk for:

- 75% chance of developing cartilage degeneration within 5 years to medial femoral condyle

- 50% chance of developing cartilage degeneration within 5 years to patella

How does a PCL tear differ to an ACL tear?

- The PCL is injured typically when there is a strong impact on the tibia pushing it backwards such as falling directly onto the knee or hitting the tibia on the dashboard whereas the ACL is torn by a non-contact twisting knee injury

- PCL tears are most commonly partial tears whereas ACL tears tend to be complete tears

- When the PCL is injured the pain and swelling is not as severe as when the ACL is injured

- That is why many PCL injuries present late once secondary damage have occurred and become symptomatic such as meniscal and cartilage degenerative changes

- On the other hand since ACL tears tend to be complete and present straight away with instability patients seek early medical consultation

- The PCL is much thicker and therefore much stronger than the ACL requiring a lot more force to injure it

- A far greater proportion of PCL injuries can be managed non-surgically in a suitable knee brace and intensive physiotherapy whereas most ACL tears will need reconstruction